Emissions Control Zones

Summary

We have captured whether or not your neighbourhood is within, partially within, or outside the London Congestion Charging Zone (LCCZ), the Low Emissions Zone (LEZ) and the Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ).

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

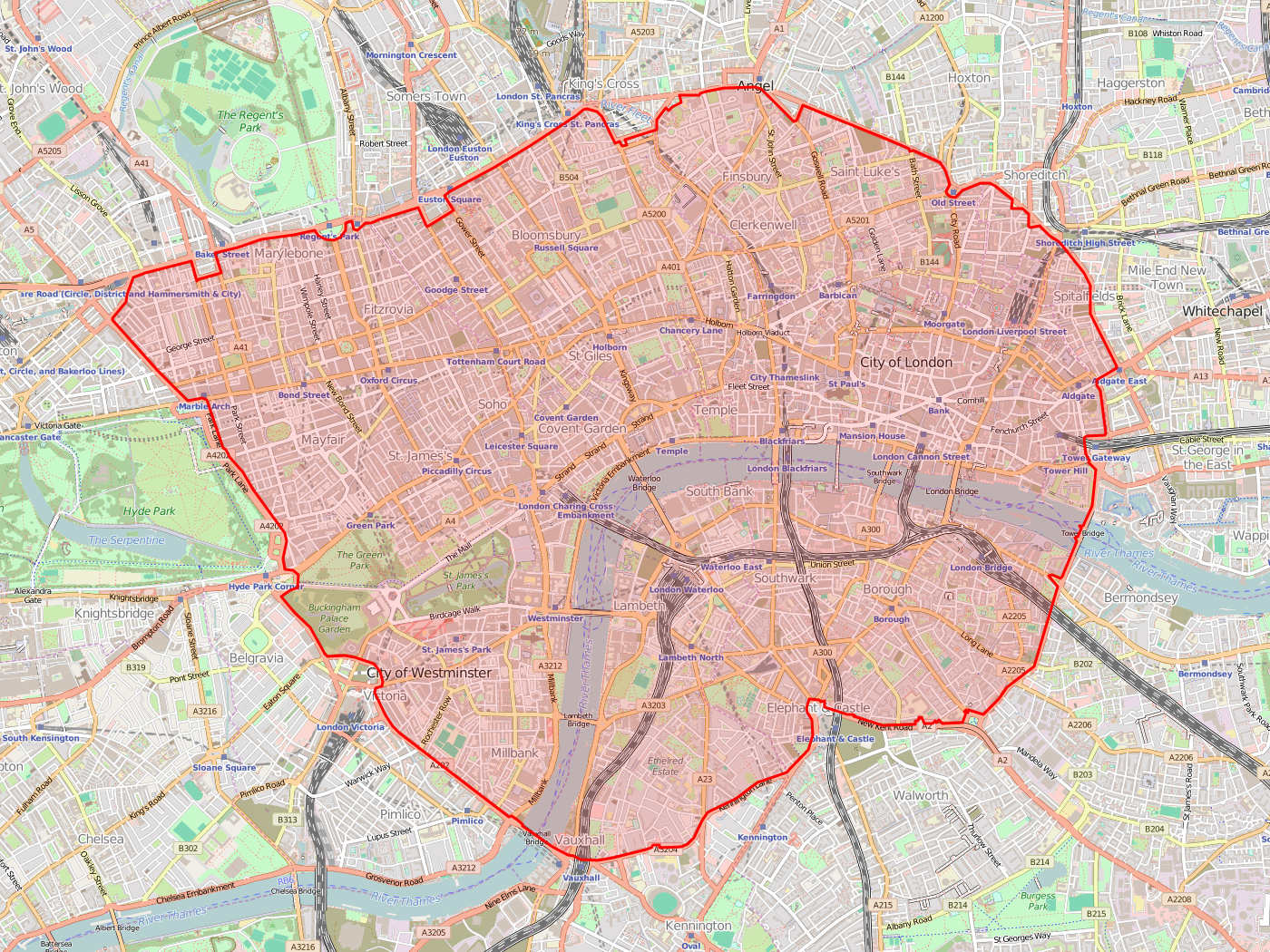

| LCCZ | Introduced in February 2003, and covers London’s central business district, being an area of 8 square miles. All vehicles entering the zone are required to pay a daily fee during business hours (07:00 to 22:00). The fee is currently £15. Electric vehicles are exempt until 2025, and NHS and care workers are exempt from the charge. |

| LEZ | The LEZ covers the vast majority of Greater London and runs 24/7. It was introduced in 2008, and applies to large and regular commercial vehicles which fall below the Euro 6 category of the European emission standards. The penalty for not reaching this standard is £100 per day for large commercial vehicles, and £300 per day for regular commercial vehicles. This does not apply to cars and motorcycles, or vans under 3.5 tonnes. |

| ULEZ | This zone was expanded in August 2023 to cover all roads within Greater London, and applies 24/7 (except Christmas Day) to all vehicles that don’t reach or exceed a certain standard set out by the European emission standards. Failure to do so results in a £12.50 charge each day a non-compliant vehicle is driven within the zone. Motorbikes must meet level 3, petrol cars/vans level 4, diesel cars/vans level 6, and all larger vehicles level 6. These larger vehicles face a £100 fine per day should they not meet these standards. |

We have numerically classified each postcode in London to as follows:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCCZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is within the LCCZ | This means that at least part of this postcode is within the LCCZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is outside of the LCCZ |

| LEZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is within the LEZ | This means that at least part of this postcode is within the LEZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is outside of the LEZ |

| ULEZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is within the ULEZ | This means that at least part of this postcode is within the ULEZ | This means that the entirety of this postcode is outside of the ULEZ |

Why the metric matters from a commercial inhabitant’s perspective

This metric has the most impact for businesses which rely on being accessed by or physically accessing goods, people or services. Whilst freight operators with more than six vehicles are eligible for a fleet discount of £1 per vehicle per day, those who cannot benefit from the fleet discount such as for example, smaller retailers of goods and services such as grocers and hairdressers, or local market professional services law firms and accountants, might have to be more creative about how their customer base accesses them, how they receive stock, etc. Being located within the LCCZ, LEZ or ULEZ will also have an impact for wholesalers who rely on retailers being able to attend their premises and the retailers who can no longer frequent these premises during standard business hours without incurring a cost.

Evidence has shown that the restrictions on operation that the zones place on businesses has led to certain employers needing increased numbers of employees to work outside the standard working week and minimise the passthrough costs of the charge. Commercial tenants will need to consider the long-term impacts of this increased out of hours economic activity. Evidence shows it can lead to issues in recruiting and retaining staff, especially quality staff. Both the congestion charge itself and the cost this poses to commercial tenants and the lower wages often offered to out of hours staff can put pressure on wages.

Yet, there is evidence of structural changes in particular a decline in the proportion of enterprises with less than 5 employees in the central zone but we do not know that the zones caused this just that they happened in tandem. There was an equal and opposite increase in employment in larger firms and in addition a stronger employment performance in the LCCZ (notwithstanding that there was an absolute decline) than other parts of London.

Therefore commercial tenants who are small businesses may wish to consider whether they feel the costs of the congestion charge on their business disproportionately when compared to other businesses and how they might counter this effect.

Why the metric matters from a residential inhabitant’s perspective

Residents will have to weigh up the net benefit or detriment to them of having reduced traffic flowing through their locale, making journeys more efficient when they do need to make them, versus being unable to use their own car during standard working hours without incurring a cost. The cost / benefit will be different for each postcode, as dictated by its existing public transport network, existing parking costs and restrictions, availability of parking and access to arterial roads and motorways.

Studies also show that residential inhabitants will find not just their commuting and general working habits impacted but their access to social networks and ability to care for and receive care from family members. Transport economists have generally supported the use of congestion charging policies to stimulate the use of more efficient transport systems, whilst reducing congestion and the ensuing pollution it causes, which should deliver a net benefit to residential inhabitants.

However, the introduction of the zones has been shown to have some adverse impacts on individuals’ levels of social support and interaction, and their abilities to invest in activities which could create such support and interaction. For example, studies have shown that the western extension of the LCCZ in particular, halved and in some cases quartered social visits and access to familial care. This of course has an impact on the need to access care elsewhere, such as from local hospitals, nursing homes etc, so has an economic impact on residents as well as on the amenity value they experience from their neighbourhoods.

The introduction of zones has also been shown on some measures to create something of an “us and them” mind set when residents outside of them consider visiting London. It can be viewed as a tax on peoples’ ability to access public places which their tax money contributes to. This of course will be felt more deeply by less affluent members of society from whom the charge will be a greater consideration. That said, the positive environmental and congestion-based impact cannot be understated, with the initial ULEZ boundary alone reducing emissions across central London by 20% in just four months.

The Congestion Charge Zone

Commentary

Evidence suggests that the introduction of the LCCZ was successful in achieving its principle aim of reducing traffic volumes and therefore congestion.

In 2013 TfL published a review of the scheme and its findings were that there had been a 10% reduction in traffic volumes in this period, and an overall reduction of 11% in vehicle kilometres in London between 2000 and 2012. Despite these gains, traffic speeds have also been getting progressively slower over the past decade, particularly in central London. TfL’s explanation is that this is caused by interventions that have reduced the effective capacity of the road network to improve the urban environment, such as increased road safety, encouraging the use of and improving public transport, and encouraging pedestrian and cycle traffic. TfL also blames an increase in road works by utilities and general development activity since 2006. TfL concludes that while levels of congestion in central London are close to pre-charging levels, the effectiveness of the congestion charge in reducing traffic volumes means that conditions would be worse without the LCCZ.

TfL’s findings also provided qualitative evidence of a decline in retail sales and an increase in costs that were attributed to the congestion charge. Even given the potential for bias in a more subjective survey there is evidence that it was believed within the retail sector that the charge impacted it adversely.

However, studies have shown that the net impact on businesses from the introduction of the LCCZ has been neutral. While the number of enterprises in the LCCZ declined in absolute terms in 2003 whilst increasing elsewhere, this was the continuation of an existing trend.

Trivia

During the first ten years since the introduction of the scheme, gross revenue reached about £2.6 billion up to the end of December 2013. From 2003 to 2013, about £1.2 billion (46%) of net revenue has been invested in public transport, road and bridge improvement and walking and cycling schemes. Of these, a total of £960 million was invested on improvements to the bus network.

History

Congestion charging was introduced into central London in February 2003 and was intended to contribute to four of the then Mayor of London Ken Livingston’s transport priorities: to reduce congestion; to make radical improvements in bus service; to improve journey reliability for car users; and to make the distribution of goods and services more efficient. At that time the charge was £5 per diem.

The price steadily increased to £8 in April 2005 and currently stands at £15. The charge is paid for driving, or parking, a vehicle inside the LCCZ, irrespective of the length of time the vehicle is inside the zone. At the time officials from 30 other British cities were reported to be considering introducing congestion charges if London’s scheme was successful. No other British cities have adopted congestion schemes since London.

Prior to the 2004 mayoral elections, proposals were drawn up to consider expanding the zone to include boroughs to the west, to include the more residential areas. The new, larger, zone included an additional 80,000 residents, taking the overall number of affected individuals to around 230,000. Some two and a half years after the initial consultation, in February 2007, the Western Extension Zone (WEZ) was formally implemented.

The extension proved particularly unpopular with residents and there was some evidence that it caused particular detriment to businesses in this area. Following public consultation, the WEZ was subsequently removed in January 2011 by Boris Johnson, after 62% of respondents backed this motion.

The ULEZ came into place in 2019, introduced by London Mayor Sadiq Khan. This was expanded in October 2021 to cover all roads within the North and South Circular. As a result of this and the LEZ, between 2016 and 2020 pollution fell five times as fast in central London as it did in other parts of the UK.